Better Nutrition for a Healthier Maryland

The terms food and nutrition are closely related and often used interchangeably, but there is an important difference between the concepts, one that significantly influences and informs the future direction of the Maryland Food Bank’s efforts to end hunger for more Marylanders.

While MFB Founder Ann Miller recognized the power that food had to change the course of people’s lives, not much thought was given to the food that was distributed early on in the organization’s history.

During those early years, food assistance was transactional — the food that was donated by the public or rescued from local retailers were the items that were given out to help hungry individuals get through what were thought to be short-term challenges with food insecurity. In fact, Miller believed the food bank would only last a few years.

Hunger Affects Marylanders Differently

But as the food bank became more sophisticated, we realized that hunger was a much bigger and much more complex issue, one that would require more than simple calories if we were truly going to impact lives. And as we began to understand our neighbors better, it became evident that there were different root causes of hunger that affect Marylanders in different ways:

- People living in Baltimore City face different barriers to food security than Marylanders across the Bay Bridge or in the Western mountains

- Younger people experience different negative consequences than older individuals

- Unemployed people experience different challenges than those with lower-wage jobs, and

- People managing chronic health conditions have different needs than their healthier neighbors

Over our 42-year history, we’ve learned that being able to provide solutions for a wide array of food-related needs requires different approaches if we’re going to truly dismantle the barriers that prevent food-insecure Marylanders from living their healthiest lives.

Barriers to Food Security

Maryland continues to be one of the wealthiest states in the nation, yet hunger persistently constrains our urban, suburban, and rural communities statewide. Poverty, low-paying jobs, and rising costs continue to disrupt the lives of far too many Marylanders and gives hunger a stronghold.

Through their most recent “ALICE” Report (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) the United Way of Central Maryland estimates that nearly 4 in 10 Marylanders are unable to support a “survival budget,” and can’t afford to pay for the basics like childcare, housing, healthcare, transportation, bills, or food.

A wide array of Marylanders — demographically, geographically, and socially that fit the United Way’s definition of “ALICE” — live in each of the 22 jurisdictions we supply food to. But some barriers can be more difficult to overcome than others.

Changing Minds, Changing Communities

Many people have heard the term “food deserts,” which the USDA defines as “low-income tracts in which a substantial number or proportion of the population has low access to supermarkets or large grocery stores.”

But this thinking is desperately in need of change — it is a reductive, negative view, focusing on what is lacking, rather than what is possible for these strong and proud communities that deserve better.

Regardless of the terminology, we know for a fact that this barrier exists more often in lower-income areas, and disproportionally in Communities of Color. People living in these areas can become entrenched in generational cycles of food insecurity.

In fact, an emerging line of thinking questions whether a person’s zip code may be more important to their health than their genetic code. But how could this be?

When people don’t have the ability to choose their foods — such as fresh fruits and vegetables — they rely on what is available, and that tends to be inexpensive and low nutritional value foods from corner and convenience stores.

But food pantries can, and do, offer choice to food-insecure Marylanders.

Picture the last time you went into a Royal Farms, 7-11, or similar store — aside from a few bananas or apples near the register, how much fresh food was available? How much processed, sugary, salty food was available?

Now imagine that store is the main source of nutrition for your family.

As those limited choices begin to add up, residents face the very real possibility of a shorter life span, heavily influenced by the non-medical factors surrounding where they live, work, learn, and play. Known as the Social Determinants of Health, these factors have an outsized influence on the quality of life for people, accounting for between 30-55 percent of health outcomes, according to the World Health Organization.

“We believe all Marylanders — regardless of level of income, education, or ethnicity — should be able to make informed choices that lead to a long and healthy life and are using our decades of experience and statewide reach to help make it a reality.”

In a stark example of how much of a role these social determinants can play, the Baltimore Sun published the results of a 2008 Baltimore City Health Department (BCHD) study that found in “West Baltimore’s impoverished Hollins Market neighborhood,” the average life span is 63 years, compared to “wealthy Roland Park, where residents live on average to be 83.” Although a BCHD follow-up study one decade later showed some improvement — residents of the Hollins Market area could expect to live 68 years — that’s still far shorter than the average 84-year life span in Roland Park.

While there were factors other than food involved in the studies, we know the power food has to fuel change, and we see a very real opportunity to lift up these communities with holistic solutions.

“We have been diligently working to increase the nutritional quality of the food we’re distributing because we know that if we don’t address the issue of nutrition now, we’re simply kicking the problem down the road, leaving it up to our healthcare system to address later on.”

And going forward additional economic and demographic data points will help us identify some of areas where stubborn hunger is hiding in our communities, including the Communities of Color that are most disproportionally affected by systemic barriers to food equality.

Pre-pandemic Progress

Over the past four decades, we’ve made great strides in helping our neighbors in need have more consistent access to healthy foods, and help teach them how to use it, and we’re proud that 2021 marks the 10-year anniversary of two of our most impactful programs, Farm to Food Bank and Pantry on the Go.

One of our most reliable sources for fresh produce, the Farm to Food Bank program works with nearly 60 Maryland farms to supply millions of pounds of fruits and vegetables grown right in our state.

Our Pantry on the Go Program, meanwhile, offers relief to our neighbors in need who live in rural, suburban, and urban areas where access to good food is limited. This initiative works with community organizations to host mobile pantries that distribute thousands of pounds of food, including fresh produce to local food-insecure residents.

Organizationally, we’ve made a commitment to utilizing data to make better informed programmatic decisions as well. The Maryland Food Bank is using more comprehensive data in our own Maryland Hunger Map to identify neighborhoods where the need outpaces available resources and redefine the generational hunger narratives that individuals face by equalizing access to nutritious foods in these areas.

Nutrition education, whether in the form of healthy cooking videos, materials distributed through our Community Hunger Intervention Programs (such as Pantry On The Go, Summer Clubs, Supper Clubs, School Pantries, HEART Markets, and the Farm to Food Bank Program), or webinars with our Network Partners, was also and continues to be a key tool in our arsenal.

In the mid 2010’s, the Maryland Food Bank, alongside many of our sister food banks, also used Feeding America’s “Foods to Encourage” (FTE) system to help better evaluate and categorize the types of food in their inventories.

Foods to Encourage used three broad categories:

- Foods to Encourage – things like cereal, fruits, juice, dairy, meat/fish/poultry, and rice

- Other Food – items including bread, prepared foods, snack foods and desserts

- Non-Food – commodities such as cleaning products, health & beauty items, and pet items

Foods to Encourage also used educational materials to get food pantries and their visitors to think more about the nutritional quality of food.

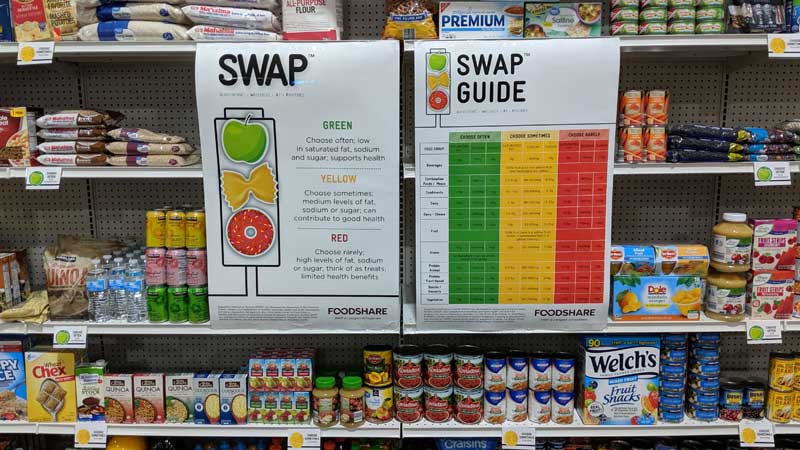

While Foods to Encourage laid a solid foundation for improving nutrition, we see exponential potential in a newer, more impactful system called SWAP, which stands for Supporting Wellness at Pantries, and uses an easy-to-follow “stoplight” system of ranking foods based on their nutritional level. And to help us increase nutrition education and integrate SWAP throughout our statewide network of community partners, we brought on experienced community nutritionist, Kate Long as a full-time MFB staff member.

“When food comes through our doors, we give it a color based on levels of sodium, saturated fat, and sugar — green means people can choose those foods often, yellow represents items to be chosen sometimes, and the red identifies foods that people should only rarely choose.”

SWAP guides our partners to make healthier choices when ordering from our menu; simplifies things for individuals and families receiving food from those partners; and helps food donors identify the types of items most beneficial for food-insecure Marylanders.

And given the reduced volume of donated food we’re continuing to see since the pandemic, our ability to continue to offer more “green” foods is only limited by our ability to keep the level of purchased food this high.

In our next blog, we’ll explore how the Maryland Food Bank was able to safely continue our efforts to improve nutrition for more Marylanders during COVID-19, and what the increased expense of having to purchase more food means for our efforts going forward.

Get updates on our progress in the fight against hunger

Want to see how your involvement directly impacts the well-being of your neighbors in need? Get the latest news sent to your inbox.